By David Milliken and Farouq Suleiman

LONDON (Reuters) – The Bank of England raised its key interest rate by a further half-percentage point on Thursday and indicated more hikes were likely, but investors bet that the central bank might be getting close to the end of its increases in borrowing costs.

The BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee voted 6-3 to raise Bank Rate to 3.5% – its highest since 2008 – from 3.0% as it eyed the risk of persistent domestic inflation pressure from prices and wages, even with a looming recession and hopes that inflation might have peaked when it hit a 41-year high in October.

But only one policymaker, Catherine Mann, wanted to match November’s bigger 0.75 percentage point increase – the BoE’s largest in more than 30 years – and two MPC members voted not to raise rates at all.

Sterling weakened by around a cent against the U.S. dollar after the BoE’s announcement, falling below $1.23, and also sagged against the euro. British government bond yields slipped on bets that rates would rise less than previously thought.

“The extent of the divisions across the committee is an eye-opener,” Philip Shaw, an economist with Investec, said. “While it is normal to see policymakers disagree towards the end of a rate cycle, the split makes it more difficult to predict the extent to which interest rates will rise.”

Some economists now think the BoE could end its programme of rate rises as soon as the first quarter of next year, having now raised nine times since December 2021 when they were at a rock-bottom 0.1%.

On Wednesday, the U.S. Federal Reserve also slowed the pace of its rate hikes while pointing to more tightening in 2023.

Shortly after the BoE’s announcement of its ninth rate hike in a row, the European Central Bank said it was also raising rates by half a percentage point and that further increases were likely.

Western central banks are grappling with post-COVID labour shortages and the inflationary impact on energy prices of Russia’s war in Ukraine while also worrying about the risks of recession.

“The labour market remains tight and there has been evidence of inflationary pressures in domestic prices and wages that could indicate greater persistence and thus justifies a further forceful monetary policy response,” the BoE said.

The BoE statement did not repeat unusual language from November which said rates were unlikely to need to rise as far as markets expected.

Market rate expectations have fallen since then, and after Thursday’s decision these showed investors expected rates to peak at 4.5% in June 2023, slightly lower than before.

The two policymakers who voted for no rate hike at all, Silvana Tenreyro and Swati Dhingra, said the tightening of monetary policy to date was “more than sufficient” to get inflation back to target.

UniCredit economist Daniel Vernazza said the BoE’s tightening cycle was coming to a close, forecasting two more quarter-point rate rises in February and March, and rate cuts beginning in the second quarter of 2024.

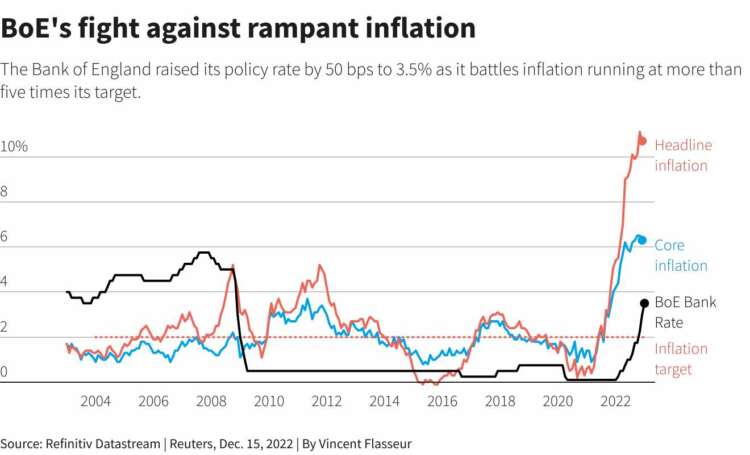

GRAPHIC: BoE’s fight against rampant inflation – https://www.reuters.com/graphics/BRITAIN-BOE/dwvkddzzgpm/chart.png

INFLATION PEAKING?

BoE Governor Andrew Bailey, in a letter to finance minister Jeremy Hunt accompanying the decision, said the BoE’s forecasts suggested British inflation had reached its peak.

Official figures on Wednesday showed consumer price inflation fell to 10.7% in November from 11.1% in October. That 0.4 percentage point fall in the annual rate was the largest since July 2021.

Speaking later to reporters, Bailey said that data gave “the first glimmer” that inflation would fall sharply next year, but said labour market pressures meant it was too soon for the BoE to let down its guard.

“That’s why really we had to raise interest rates today, because we see that risk as really quite pronounced,” he said.

Britain is in the midst of a wave of industrial action, and nominal pay excluding bonuses rose at the fastest pace since 2001 in the three months to the end of October.

An energy price cap in Hunt’s November fiscal statement meant inflation in the second quarter of next year would be 0.75 percentage points lower than the BoE had forecast, but the longer-term impact would be minimal, the BoE said.

Last month the BoE said Britain was entering a long recession, and predicted the economy would shrink by 0.3% in the final quarter of this year.

Now it expects a fall of 0.1%, and for economic output in a year’s time to be 0.4% higher than previously thought as a result of budget measures that offered short-term stimulus.

But fiscal tightening further ahead would leave gross domestic product in two years’ time little changed from the BoE’s November projections, and 0.5% lower in three years’ time than it had forecast.

Government budget forecasters have warned that households face the biggest squeeze on living standards since records began in the 1950s, and the OECD forecasts Britain’s GDP will fall more than for any economy except Russia’s next year.

The BoE is also pressing on with its plans to reduce its 831 billion pound ($1.02 trillion) quantitative easing stockpile by 80 billion pounds in the space of a year. Gilt sales for the first quarter of 2023 will be announced at 1800 GMT on Friday.

($1 = 0.8121 pounds)

(Additional reporting by Andy Bruce; Editing by William Schomberg, Hugh Lawson and Catherine Evans)